|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Protein analysis: Protein separation and characterization

In the previous section, techniques used to determine the total

concentration of protein in a food were discussed. Food analysts are also often

interested in the type of proteins present in a food because each

protein has unique nutritional and physicochemical properties. Protein type is

usually determined by separating and isolating the individual proteins

from a complex mixture of proteins, so that they can be subsequently identified

and characterized. Proteins are separated on the basis of differences in their

physicochemical properties, such as size, charge, adsorption characteristics,

solubility and heat-stability. The choice of an appropriate separation

technique depends on a number of factors, including the reasons for

carrying out the analysis, the amount of sample available, the desired purity,

the equipment available, the type of proteins present and the cost. Large-scale

methods are available for crude isolations of large quantities of proteins,

whereas small-scale methods are available for proteins that are expensive or

only available in small quantities.

Proteins can be separated by exploiting differences in their solubility in aqueous solutions. The solubility of a protein molecule is determined by its amino acid sequence because this determines its size, shape, hydrophobicity and electrical charge. Proteins can be selectively precipitated or solubilized by altering the pH, ionic strength, dielectric constant or temperature of a solution. These separation techniques are the most simple to use when large quantities of sample are involved, because they are relatively quick, inexpensive and are not particularly influenced by other food components. They are often used as the first step in any separation procedure because the majority of the contaminating materials can be easily removed. Salting outProteins are precipitated from aqueous solutions when the salt concentration exceeds a critical level, which is known as salting-out, because all the water is "bound" to the salts, and is therefore not available to hydrate the proteins. Ammonium sulfate [(NH4)2SO4] is commonly used because it has a high water-solubility, although other neutral salts may also be used, e.g., NaCl or KCl. Generally a two-step procedure is used to maximize the separation efficiency. In the first step, the salt is added at a concentration just below that necessary to precipitate out the protein of interest. The solution is then centrifuged to remove any proteins that are less soluble than the protein of interest. The salt concentration is then increased to a point just above that required to cause precipitation of the protein. This precipitates out the protein of interest (which can be separated by centrifugation), but leaves more soluble proteins in solution. The main problem with this method is that large concentrations of salt contaminate the solution, which must be removed before the protein can be resolubilzed, e.g., by dialysis or ultrafiltration. Isoelectric PrecipitationThe isoelectric point (pI) of a protein is the pH where the net charge on the protein is zero. Proteins tend to aggregate and precipitate at their pI because there is no electrostatic repulsion keeping them apart. Proteins have different isoelectric points because of their different amino acid sequences (i.e., relative numbers of anionic and cationic groups), and thus they can be separated by adjusting the pH of a solution. When the pH is adjusted to the pI of a particular protein it precipitates leaving the other proteins in solution. Solvent FractionationThe solubility of a protein depends on the dielectric constant of the solution that surrounds it because this alters the magnitude of the electrostatic interactions between charged groups. As the dielectric constant of a solution decreases the magnitude of the electrostatic interactions between charged species increases. This tends to decrease the solubility of proteins in solution because they are less ionized, and therefore the electrostatic repulsion between them is not sufficient to prevent them from aggregating. The dielectric constant of aqueous solutions can be lowered by adding water-soluble organic solvents, such as ethanol or acetone. The amount of organic solvent required to cause precipitation depends on the protein and therefore proteins can be separated on this basis. The optimum quantity of organic solvent required to precipitate a protein varies from about 5 to 60%. Solvent fractionation is usually performed at 0oC or below to prevent protein denaturation caused by temperature increases that occur when organic solvents are mixed with water. Denaturation of Contaminating ProteinsMany proteins are denatured and precipitate from solution when heated above a certain temperature or by adjusting a solution to highly acid or basic pHs. Proteins that are stable at high temperature or at extremes of pH are most easily separated by this technique because contaminating proteins can be precipitated while the protein of interest remains in solution.

Adsorption chromatography involves the separation of compounds by selective adsorption-desorption at a solid matrix that is contained within a column through which the mixture passes. Separation is based on the different affinities of different proteins for the solid matrix. Affinity and ion-exchange chromatography are the two major types of adsorption chromatography commonly used for the separation of proteins. Separation can be carried out using either an open column or high-pressure liquid chromatography. Ion Exchange ChromatographyIon exchange chromatography relies on the reversible adsorption-desorption of ions in solution to a charged solid matrix or polymer network. This technique is the most commonly used chromatographic technique for protein separation. A positively charged matrix is called an anion-exchanger because it binds negatively charged ions (anions). A negatively charged matrix is called a cation-exchanger because it binds positively charged ions (cations). The buffer conditions (pH and ionic strength) are adjusted to favor maximum binding of the protein of interest to the ion-exchange column. Contaminating proteins bind less strongly and therefore pass more rapidly through the column. The protein of interest is then eluted using another buffer solution which favors its desorption from the column (e.g., different pH or ionic strength). Affinity ChromatographyAffinity chromatography uses a stationary phase that consists of a ligand covalently bound to a solid support. The ligand is a molecule that has a highly specific and unique reversible affinity for a particular protein. The sample to be analyzed is passed through the column and the protein of interest binds to the ligand, whereas the contaminating proteins pass directly through. The protein of interest is then eluted using a buffer solution which favors its desorption from the column. This technique is the most efficient means of separating an individual protein from a mixture of proteins, but it is the most expensive, because of the need to have columns with specific ligands bound to them. Both ion-exchange and affinity chromatography are commonly used to separate proteins and amino-acids in the laboratory. They are used less commonly for commercial separations because they are not suitable for rapidly separating large volumes and are relatively expensive.

Proteins can also be separated according to their size. Typically, the molecular weights of proteins vary from about 10,000 to 1,000,000 daltons. In practice, separation depends on the Stokes radius of a protein, rather than directly on its molecular weight. The Stokes radius is the average radius that a protein has in solution, and depends on its three dimensional molecular structure. For proteins with the same molecular weight the Stokes radius increases in the following order: compact globular protein < flexible random-coil < rod-like protein. DialysisDialysis is used to separate molecules in solution by use of semipermeable membranes that permit the passage of molecules smaller than a certain size through, but prevent the passing of larger molecules. A protein solution is placed in dialysis tubing which is sealed and placed into a large volume of water or buffer which is slowly stirred. Low molecular weight solutes flow through the bag, but the large molecular weight protein molecules remain in the bag. Dialysis is a relatively slow method, taking up to 12 hours to be completed. It is therefore most frequently used in the laboratory. Dialysis is often used to remove salt from protein solutions after they have been separated by salting-out, and to change buffers. UltrafiltrationA solution of protein is placed in a cell containing a semipermeable membrane, and pressure is applied. Smaller molecules pass through the membrane, whereas the larger molecules remain in the solution. The separation principle of this technique is therefore similar to dialysis, but because pressure is applied separation is much quicker. Semipermeable membranes with cutoff points between about 500 to 300,000 are available. That portion of the solution which is retained by the cell (large molecules) is called the retentate, whilst that part which passes through the membrane (small molecules) forms part of the ultrafiltrate. Ultrafiltration can be used to concentrate a protein solution, remove salts, exchange buffers or fractionate proteins on the basis of their size. Ultrafiltration units are used in the laboratory and on a commercial scale. Size Exclusion ChromatographyThis technique, sometimes known as gel filtration, also separates proteins according to their size. A protein solution is poured into a column which is packed with porous beads made of a cross-linked polymeric material (such as dextran or agarose). Molecules larger than the pores in the beads are excluded, and move quickly through the column, whereas the movement of molecules which enter the pores is retarded. Thus molecules are eluted off the column in order of decreasing size. Beads of different average pore size are available for separating proteins of different molecular weights. Manufacturers of these beads provide information about the molecular weight range that they are most suitable for separating. Molecular weights of unknown proteins can be determined by comparing their elution volumes Vo, with those determined using proteins of known molecular weight: a plot of elution volume versus log(molecular weight) should give a straight line. One problem with this method is that the molecular weight is not directly related to the Stokes radius for different shaped proteins.

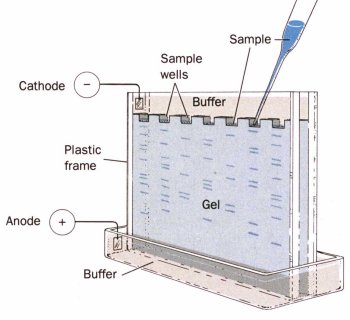

Non-denaturing ElectrophoresisIn non-denaturing electrophoresis, a buffered solution of native proteins is poured onto a porous gel (usually polyacrylamide, starch or agarose) and a voltage is applied across the gel. The proteins move through the gel in a direction that depends on the sign of their charge, and at a rate that depends on the magnitude of the charge, and the friction to their movement:

Proteins may be positively or negatively charged in solution depending on their isoelectic points (pI) and the pH of the solution. A protein is negatively charged if the pH is above the pI, and positively charged if the pH is below the pI. The magnitude of the charge and applied voltage will determine how far proteins migrate in a certain time. The higher the voltage or the greater the charge on the protein the further it will move. The friction of a molecule is a measure of its resistance to movement through the gel and is largely determined by the relationship between the effective size of the molecule, and the size of the pores in the gel. The smaller the size of the molecule, or the larger the size of the pores in the gel, the lower the resistance and therefore the faster a molecule moves through the gel. Gels with different porosity's can be purchased from chemical suppliers, or made up in the laboratory. Smaller pores sizes are obtained by using a higher concentration of cross-linking reagent to form the gel. Gels may be contained between two parallel plates, or in cylindrical tubes. In non-denaturing electrophoresis the native proteins are separated based on a combination of their charge, size and shape. Denaturing ElectrophoresisIn denaturing electrophoresis proteins are separated primarily on their molecular weight. Proteins are denatured prior to analysis by mixing them with mercaptoethanol, which breaks down disulfide bonds, and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), which is an anionic surfactant that hydrophobically binds to protein molecules and causes them to unfold because of the repulsion between negatively charged surfactant head-groups. Each protein molecule binds approximately the same amount of SDS per unit length. Hence, the charge per unit length and the molecular conformation is approximately similar for all proteins. As proteins travel through a gel network they are primarily separated on the basis of their molecular weight because their movement depends on the size of the protein molecule relative to the size of the pores in the gel: smaller proteins moving more rapidly through the matrix than larger molecules. This type of electrophoresis is commonly called sodium dodecyl sulfate -polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, or SDS-PAGE. To determine how far proteins have moved a tracking dye is added to the protein solution, e.g., bromophenol blue. This dye is a small charged molecule that migrates ahead of the proteins. After the electrophoresis is completed the proteins are made visible by treating the gel with a protein dye such as Coomassie Brilliant Blue or silver stain. The relative mobility of each protein band is calculated:

Electrophoresis is often used to determine the protein composition of food products. The protein is extracted from the food into solution, which is then separated using electrophoresis. SDS-PAGE is used to determine the molecular weight of a protein by measuring Rm, and then comparing it with a calibration curve produced using proteins of known molecular weight: a plot of log (molecular weight) against relative mobility is usually linear. Denaturing electrophoresis is more useful for determining molecular weights than non-denaturing electrophoresis, because the friction to movement does not depend on the shape or original charge of the protein molecules. back to top of

page |